Nathan Fielder, Andy Kaufman, and the Ethical Stakes of Comedic Kayfabe

How The Rehearsal Revives Kaufman’s Favorite Trick: Making the Entire World the Punchline

[Spoilers for Season 2 of HBO’s The Rehearsal]

Did you hear the news, Nathan Fielder flew a 737 full of passengers? Oh but actually it was a plane full of actors, and it's likely that he had practiced with empty planes beforehand, and we know he survived because we would have heard about the crash. We’re pretty sure he actually learned to fly a plane, at least.

If you finished the most recent season of Fielder’s show The Rehearsal, you might’ve felt like me, stunned and a bit whiplashed trying to wrap your head around what you just saw, or more specifically—the degree to which what you just saw was real. Fielder began the season with the premise that he wanted to use his recursive simulation scenarios or rehearsals to help minimize aviation disasters caused by lack of communication between pilots and co-pilots. This led to Fielder re-enacting the life of Sully Sullenberger, creating a fake singing competition, and by the end, earning a pilot’s license and successfully flying a Boeing 737 full(?) of actor-passengers.

Of course, this is not a new phenomenon. Fielder’s entire project is built on the audience’s inability to cleanly distinguish what’s real from what’s not. This uncertainty isn’t just for comedic effect—it’s ethical. It makes viewers more attuned to the constructed nature of the scenarios and intensifies the stakes of what unfolds within them. As viewers oscillate between analyzing Fielder's intentions and immersing themselves in the narrative, a larger question emerges: Is it ethical to trick people into participating in something they don’t, and perhaps can’t, fully understand as unreal?

Multiple articles, video essays, and Reddit threads attempt to unravel the show’s layered relationship to reality and morality, often by reconstructing timelines to determine what was real and what was scripted. Fielder’s work is compelling not because it hides that boundary, but because it systematically pressures it—forcing audiences to decide where they think the line should be drawn.

For example, one participant in Fielder’s fake talent show Wings of Voice broke their NDA to testify that they’d been taken advantage of, spending thousands of dollars under the belief that they had a genuine professional opportunity. In the previous season, a child actor became emotionally attached to Fielder while they rehearsed being a family—a situation that raised broader concerns not only about Fielder’s methods, but about the ethics of child acting more generally. And in Nathan For You, Fielder convinced the owner of a struggling electronics store to exploit Best Buy’s price-matching policy by advertising TVs for a dollar, but locking them behind a maze, a strict dress code, and a live alligator. The business owner followed through on the scheme and multiple people attempted to secure a cheap T.V.—it’s unclear whether they were willing participants or suckers.

But crucially, Fielder’s work is compelling as much as is it alienating or frustrating because he does not provide his audience with any stable footing to draw the line. He continues the bit beyond the confines of the show, such as in talk show interviews and social media posts—he never steps outside the persona to tell us what was “just a joke”. In a sense, Fielder exposes that the distinction between fiction and reality is itself groundless—less a property of the world than a projection of our expectations.

As a result, public debates over what in The Rehearsal was scripted—and, by extension, what is ethically permissible—aren’t attempts to uncover the “truth” of the matter. They’re acts of collective boundary-drawing. Fielder doesn’t just obscure the line; he hands it back to us and dares us to decide where it belongs.

For pragmatists such as John Dewey, Richard Rorty, and Amie Thomasson, concepts aren’t rigid classifications handed down from on Plato’s heaven—they’re tools we use. And like any tool, they can break under pressure. In some contexts, especially novel or rapidly changing ones, the rules we usually rely on to apply a concept start to break down. Take artificial intelligence. As AI-generated images, text, and even “conversations” have grown more convincing, we’ve been forced to renegotiate whether certain artifacts should still count as art, or writing, or even expression. Is a machine-generated painting still a painting? Can it win an art prize? If it does, does that tell us something new about what we’re were committed to when we used the concept “art” all along?

If we say yes, then machines may be eligible for copyright, or authors might lose it. If we say no, we risk redefining art in a way that excludes certain human creators too, especially those who rely on tools, prompts, or collaborations. Either way, how we draw the line has implications for what we say and do, not just legally, but socially and aesthetically as well. This is why the concepts we use matter. They’re not just labels. They structure our practices, shape our institutions, and determine what we count as valuable or worth defending.

Similarly, the rules for determining what counts as “fiction” or “reality” are often partial, purpose-relative, and deeply contested. In most contexts, we this or granted—we don’t need to think about where the line is because nothing is pressing up against it. But The Rehearsal doesn’t just “blur” the line between fiction and reality. Through layered performances, recursive simulations, and ethical ambiguity, it creates a non-standard context where our usual classificatory habits break down. And in doing so, it exposes something deeper: that the fiction–reality distinction has always been more fragile than we’d like to believe.

Fielder doesn’t collapse the fiction–reality distinction, he re-engineers the context of application so the rules break down—and what once seemed obvious becomes contestable. This conceptual instability is a feature, not a bug. It forces us to ask (maybe for the first time seriously) what that distinction was doing in the first place, and whether it still works.

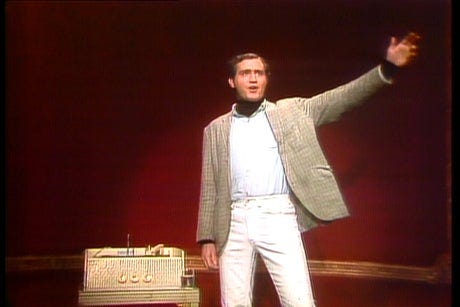

While The Rehearsal is impressive for its recursive simulations and emotional counterweighting—what stuck with me most was how much Fielder’s comedic engineering of the fiction–reality distinction reminded me of alleged comedian and Women’s Wrestling Champion of the World: Andy Kaufman.

Kaufman’s comedy is what we now call “anti-comedy”, structured to deconstruct the performance frame itself. Kaufman didn’t tell jokes, and his comedy sets or lounge singer routines weren’t him playing “characters”—they were situations that caused a breakdown in the very concepts audiences relied on to understand and evaluate what they were witnessing. He broke comedy open and weaponized his audiences’ expectations. As Robin Williams famously put it, Kaufman “made himself the premise and the entire world was the punchline.” The comedy wasn’t in what he said or did, it was in the dissonance he produced when no one could tell whether they were watching a bit, a breakdown, or something in between.

While younger people might know Kaufman from the “Mighty Mouse” sketch or his stint on Taxi, his entire comedy career is one long exercise in demolishing the foundations for any reliable distinction between fiction and reality. In that sense, Kaufman’s work is closer to conceptual art, like John Cage’s 4'33", than to conventional stand-up. Like watching The Rehearsal: “You couldn’t leave [a Kaufman] show without an opinion.”1

Likewise, Fielder’s comedy fits comfortably in the tradition of Kaufman’s and they are both distinguished by the inherent inability of the audience to discern where the persona ends and the person begins. Notably, Fielder and Kaufman are both interested in magic, and a good magic trick blends reality and the illusion in such a way we can’t help but want to know how it works. A good illusion takes us beyond the land of reality, where we’re no longer even interested in asking the question.

“Honestly, I think anything in it is up in the air as being an illusion. I don't think that makes it any less incredible though, or any less of a magic trick. The story, the statements and movement of the plot are the same regardless. Just the very form the show takes—that can leave us so confused about what's real and what's not—is brilliant.”

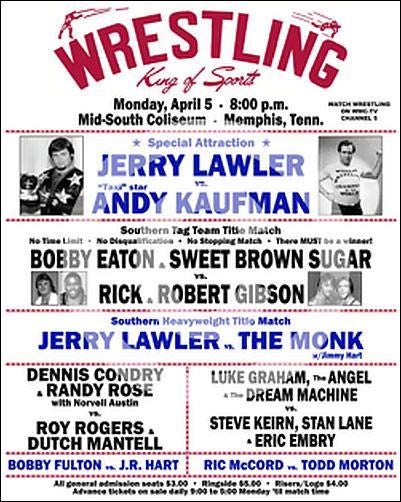

Before Fielder climbed into the cockpit of a Boeing 737, Andy Kaufman was locking women into headlocks as a self-declared “intergender” wrestling champion. Starting in the late 1970s, Kaufman began inviting women from his live shows to wrestle him on stage, offering cash (or occasionally marriage) if they could beat him. Eventually, he took the act on tour, boasting an undefeated record across more than 300 matches.

From there, Kaufman launched an extended wrestling career as a heel, embedding himself in the Memphis wrestling scene—a regional circuit known for its intense fan devotion and strict insistence on maintaining the illusion. In that world, the line between performance and reality was still treated as sacred. Kaufman played the perfect outsider villain: an arrogant, coastal elitist mocking Southern culture and taunting his audiences with cartoonish misogyny. His feud with Memphis legend Jerry Lawler became the centerpiece, culminating in a televised brawl on Late Night with David Letterman, where Lawler slapped Kaufman out of his chair. Whether, or to what extent, it was all a bit remains an open question to this day.

It should be no surprise that Kaufman was drawn to professional wrestling at a time where everyone else in Hollywood looked down on it as a lower art form. Wrestling is a genre that thrives on collapsing the boundary between fiction and reality. In fact, the wrestling world has its own term for this specific blend of persona, performance, and emotional investment: kayfabe.

“Kayfabe” is the term used in professional wrestling to name the specific blend of fiction and reality that defines the art form. It doesn’t mean “fake”—it refers to the combination of scripted narrative, physical performance, and emotional stakes that resists any clean separation between what’s real and what’s not. Like a good work of fiction, a good wrestling storyline isn’t judged by whether it’s true, but by whether it works—whether it compels belief, investment, emotion. Whether it feels real enough to matter.

The significance of kayfabe is especially clear in the wrestling promo: speeches or monologues used to hype up a feud or storyline. Take “Stone Cold” Steve Austin’s legendary “Austin 3:16” promo in 1996. It is considered one of the GOATs of promos because it feels like something spontaneous and authentic has broken through. The audience isn’t just cheering the content, they are responding to the collapse of the performance boundary in real time. The line between performance and person dissolves in the heat of the moment, and that dissolution is the aesthetic event.2

Kaufman bought local commercials in Memphis to promote his heel persona, published articles threatening to sue NBC, and blurred the boundaries between legal action, performance, and delusion. Every move he made made it harder to tell whether the whole thing was the joke—or just the delivery system. He used kayfabe to reveal the fundamental instability of the fiction–reality distinction itself. It was a conceptual magic trick, and the world was (is?) the rube.

Kaufman was the king of kayfabe, in and out of the ring. Like his alter-ego Tony Clifton, he was the heel the comedy world didn’t want, but desperately needed—capable of riling up his audiences then leaving without any resolution (but perhaps some milk and cookies). Like all great wrestling promos, the bits compelled us to ask, like David Letterman asked Jerry Lawler, “Is it fixed or not?” When Kaufman announced his retirement from wrestling, people laughed, because no one knew if he was being serious. When he died, the majority of the country didn’t believe it.

In the documentary Andy Kaufman: I’m From Hollywood Kaufman acknowledges that his wrestling career is him taking the bit as far as he can: “Going all the way with it...playing it straight to the hilt”. Friends and colleagues described their utter confusion at his commitment to wrestling, suggesting that Kaufman became “obsessed”, and the bit was a way for him to “live out his fantasies” (or “checkout with the baggage”). You could say the exact same thing about Fielder piloting a 737.3

When a performance deliberately breaks down the line between fiction and reality, it doesn’t just confuse us—it shatters the tools we normally use to make sense of the world. It exposes the limits of what we think we know, and forces us to sit with that uncertainty. You can judge Kaufman’s wrestling or Fielder’s flying to be ethically objectionable—after you’ve done the conceptual work. Until you’ve experienced the boundary break down, you’re not in a position to redraw it.

Because if we can’t settle whether Kaufman’s matches were performances, or whether Fielder actually flew the plane, we’re not in a position to make competent ethical claims about them, either. If you can’t say what kind of thing it is—performance, deception, sincerity, art, all of the above—you’re not ready to say whether it’s right or wrong.

How we answer will shape what kinds of responsibilities we assign, what sorts of harms we recognize, and what boundaries we treat as actionable—because our classifications are not neutral descriptions, but tools that license entitlements, structure accountability, and govern what follows from what.

If the conceptual precedes the ethical, then we need art that puts pressure on our concepts. That shows us that they can break. That refuses to let us off the hook.

That’s what the heel is for.

Marilu Henner. In the 1998 documentary Remembering Andy Kaufman, an interviewee describes Kaufman as a “behavioral psychologist”.

Historically, kayfabe extended outside the ring as well. Wrestlers maintained their personas in interviews, public appearances, even airports—heels didn’t fraternize with faces. Breaking character wasn’t just bad form; it threatened the integrity of the performance structure itself.

It might be that Kaufman and Fielder are also unsure where their persona ends and their person begins, and that might be why their brand of comedic kayfabe is particularly potent. I remain agnostic on the matter.